On March 7, 1965, peaceful protesters led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began a 54-mile march from Selma, Alabama, to the state's capital, Montgomery. There were 600 people marching after the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a civil rights activist and deacon in the Baptist church, who was shot to death by a state trooper as he tried to protect his mother during a civil rights demonstration. On March 7, the marchers reached the outskirts of Selma and crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they were met by state troopers, who refused to speak to the protesters and instead began attacking them. Here's how the History Channel describes it:

[State troopers] knocked the marchers to the ground. They struck them with sticks. Clouds of tear gas mixed with the screams of terrified marchers and the cheers of reveling bystanders. Deputies on horseback charged ahead and chased the gasping men, women and children back over the bridge as they swung clubs, whips and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. Although forced back, the protesters did not fight back.Millions of people watched this attack on live TV (after ABC interrupted a showing of "Judgment at Nuremberg," a movie about Nazi bigotry and atrocities), and it proved to be a turning point in getting the Voting Rights Act passed. Of note, the conservative Supreme Court recently gutted the protections enshrined in the Voting Rights Act, saying they weren't needed anymore since racism is over or whatever, and that's one major reason we have the voting nightmare we do now. It's by design, and SCOTUS gutted the oversight that could have mitigated this.

The bridge itself still stands, and is now a National Historic Landmark. But let's take a look at the name it bears: Edmund Pettus. Who was he? Well, a white guy, of course (it *is* Alabama). Pettus was a Confederate general during the U.S. Civil War. He was a leader in the Alabama KKK. He even became the Grand Dragon of the Alabama Klan in the final year of Reconstruction. At age 75, after a full life of racist "heroism," he was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served until he died in the middle of his second term. And in May 1940, decades after his death, Selma dedicated the bridge in honor of this man. Why might they do that? Well, let's ask some historians interviewed by Smithsonian Magazine:

At the time, Selma “would’ve been a place where place names were about [black people’s] degradation,” says Alabama historian Wayne Flynt. “It’s a sort of in-your-face reminder of who runs this place.”

In the program book commemorating the [May 1940] dedication, Pettus is recalled as “a great Alabamian.” Of the occasion, it was written, “And so today the name of Edmund Winston Pettus rises again with this great bridge to serve Selma, Dallas County Alabama and one of the nation’s great highways.”

So even as the bridge opened as a symbol of pride for a battered South still rebuilding decades after the Civil War, it was also a tangible link to the state’s long history of enslaving and terrorizing its black inhabitants.

“The bridge was named for him, in part, to memorialize his history, of restraining and imprisoning African-Americans in their quest for freedom after the Civil War,” says University of Alabama history professor John Giggie.Seems pretty clear to me why they named it the way they did.

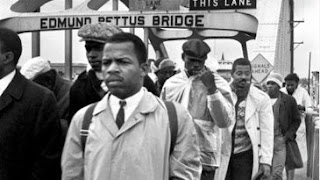

This is John Lewis.

But back to the march in 1965. Along with Dr. King and various notable figures, marching that day was 25-year-old John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). When the police attacked, Lewis was at the front of the march, and he was beaten savagely by a policeman wielding a baton. The officer hit him at least twice in the head, causing a skull fracture and nearly killing Lewis.

Yes, that's John Lewis in the foreground

being beaten by the police.

being beaten by the police.

John Lewis went on to become a congressman; he has represented Georgia since 1986. He's often called the "conscience of the U.S. Congress." He has worked tirelessly for equality and justice, and he's revered as a civil rights leader. In December 2019, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, but in March of this year, he still came to commemorate the 55th anniversary of the march in Selma. He spoke eloquently to the crowd:

Fifty-five years ago, a few of our children attempted to march ... across this bridge. We were beaten, we were tear-gassed. I thought I was going to die on this bridge. But somehow and some way, God almighty helped me here. ... We must go out and vote like we never, ever voted before. ... I'm not going to give up. I'm not going to give in. We're going to continue to fight. We need your prayers now more than ever before. We must use the vote as a nonviolent instrument or tool to redeem the soul of America. ... To each and every one of you, especially you young people. ... Go out there, speak up, speak out. Get in the way. Get in good trouble. Necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.So you tell me: What name should this bridge bear? Should we commemorate the glorified history of racist violence, subjugation, greed, and ownership of people? Or should we honor the life's work of a man who has worked tirelessly and peacefully for equality, despite having nearly lost his life to the cause? To me, it's not even a hard question. The bridge should be renamed, all the military bases that bear the names of Confederate generals should be renamed, and all the racist statues designed to intimidate should be taken down and replaced with monuments to the history of bravery shown by Americans throughout history fighting for justice and equality. Give me statues of Harriet Tubman. Give me statues of the black and brown men who have fought in every single war this country has engaged in, yet never seem to get the credit of their white brethren. Give me statues of black Civil War heroes. Give me statues of John Lewis.

No comments:

Post a Comment